Redlining and Racism – the Real Roots of Food Deserts in our Communities

By Lauren Berryman (’21), Content Development Assistant

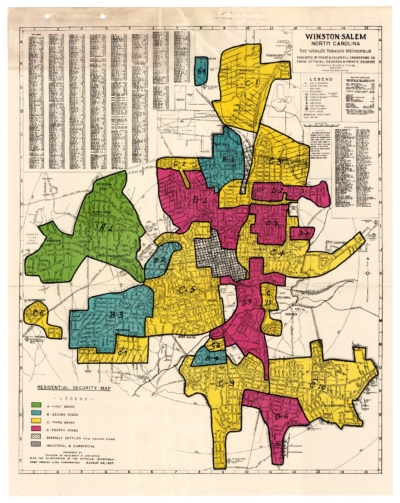

A staggering one in seven North Carolinians faces hunger, according to Feeding America. If you zoom in closer, you’ll find that 49.7% of Black residents in Winston-Salem have low or no access to healthy food. Not only that but over 20 food deserts exist in Winston-Salem, concentrated primarily on the east side of town. In these communities facing food insecurity, redlining and institutional racism are at the roots of the problem.

“Studies have indicated there are often biases against opening stores in communities of low-income and minoritized individuals based on a perception of lower profit margins,” says Brad Shugoll, Associate Director of Service and Leadership for Wake Forest’s Office of Civic and Community Engagement (OCCE). “This has amounted to structural racism and what some have called ‘supermarket redlining’.”

Winston-Salem isn’t alone in this phenomenon; it persists in predominantly Black and brown communities across the country.

For over 40 years, not a single full-service grocery store existed in West Oakland, CA. It wasn’t until the independent, grassroots-funded grocer, Community Foods Market opened its doors in June 2019 that residents in West Oakland gained access to fresh, affordable food options. CEO and social entrepreneur, Brahm Ahmadi will present the Office of Sustainability’s virtual keynote lecture on Wednesday, October 28 at 7:30 p.m about his roots in environmental justice and how he has addressed food insecurity in his community through a social entrepreneurial approach for nearly 20 years.

Like Ahmadi, local community leaders have been tackling food insecurity through a social justice lens in Winston-Salem. One such organization, SHARE Cooperative, strives to bring food equity by opening grocery stores in food deserts across Winston-Salem.

“Generally, corporations don’t put grocery stores in food deserts because they don’t trust that they can achieve their profit margins,” says SHARE AmeriCorps VISTA and former Office of Sustainability intern, Peter Schlachte. “Because of this trend, organizations have been wary of providing funds/loans for us.”

Despite an uphill battle to secure funding from such organizations, SHARE has raised nearly $2 million of the $2.4 million needed to open and operate a brick and mortar store. Part of this funding has come from the 400 Member-Owners of SHARE.

“Food is the building block from which we can build a city that is not only healthier, but is also more economically and racially just,” says Schlachte.

Food insecurity is not an easy or immediate fix, given its intersections with structural with economic inequality.

Community leader Marcus Hill has been at the helm of numerous local and national organizations, including Forsyth Foodworks, the US Solidarity Economics Network, and Island CultureZ, that aim to address food insecurity through equitable community development.

Hill explains that the high number of food deserts in Winston-Salem are due to racism, redlining and capitalism. Just east of Highway 52, which has bisected the city since the mid-20th century, are predominantly Black neighborhoods that have only two grocery stores. On the west side of town it is a completely different story. In these predominantly white, affluent neighborhoods are more than 20 grocery stores, many within just a mile of one another.

“Food justice here in Winston-Salem requires broader acknowledgment that food insecurity is a chronic social, economic, and political problem demanding long-term social, economic, and political responses,” Hill says.

This systemic issue demands long-term social, economic and political response at the local, state and national level. Becoming involved with the Wake Forest University Office of Civic and Community Engagement (OCCE) is a valuable way for students to address issues like food insecurity.

“Students could begin by engaging in direct service and learning more about our community decision making process,” says Bradley Shugoll, the Associate Director of Service and Leadership in the OCCE.

“Students should also work towards addressing the larger systemic challenges,” Shugoll says. “This means learning more about the causes of food insecurity and the role of policy decisions in creating more equitable systems.”

For more information on changing food systems through access, equity and empowerment, RSVP here for Ahmadi’s “Leadership for Environmental Justice” lecture.

Watch Ahmadi’s recorded lecture and moderated Q&A at the link below: