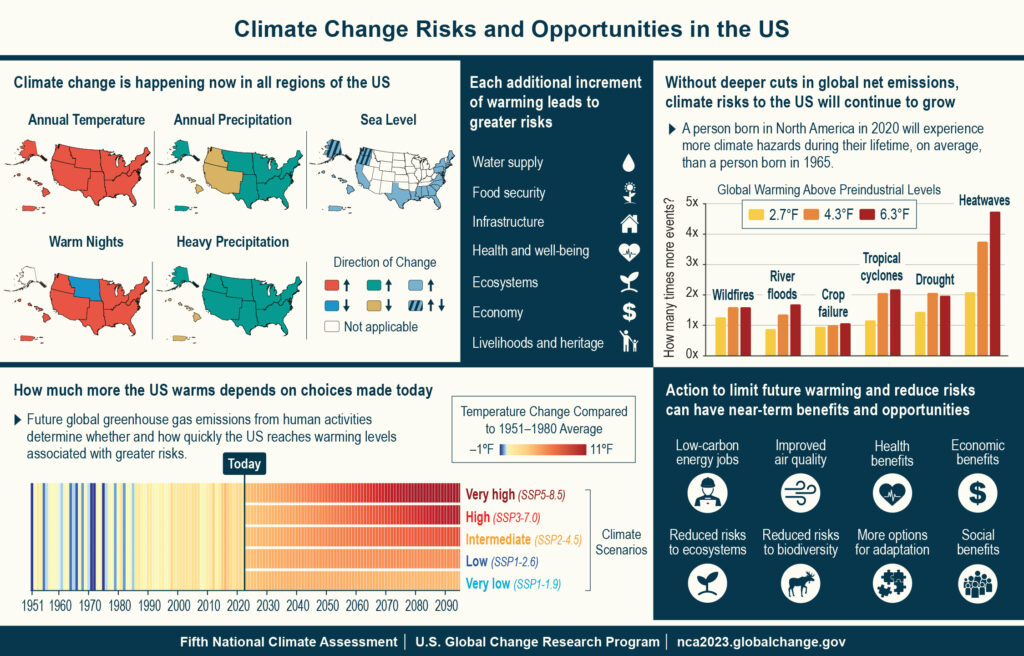

The effects of burning fossil fuels and emitting heat-trapping greenhouse gasses are vast and worsening across all regions of the United States. With the global average surface temperature already hovering around 1.2 degrees celsius (2.2 degrees F) above pre-industrial levels, some of the effects of human-made emissions are already baked in. But rapidly reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions today still has the power to limit future warming and result in immediate economic and health co-benefits.

These are just some of the findings revealed in the Fifth National Climate Assessment (NCA5) released mid-November.

The congressionally mandated assessment is the U.S. Government’s preeminent report on climate change impacts, risks, and responses. For the first time, the report includes a chapter on economic impacts and opportunities aligned with climate action, as well as a chapter on social systems and justice, further exploring how different communities experience and respond to climate change.

“There is a dire need to emphasize the multi-layered and pervasive effects of climate change on Black and Brown communities,” said Crystal T. Dixon, Associate Professor of the Practice in the Department of Health and Exercise Science and collaborative faculty member in the Program for African American Studies. “While access to urban green spaces is one mechanism to resolve adverse climate impacts, these solutions are not sufficient to address environmental racism embedded in policies and practices. It is promising that the Fifth National Climate Assessment report recognizes redlining, systemic racism, and racial discrimination as the cause of pervasive health disparities impacting Black and Brown communities.”

The report spans 32 chapters, including 10 regional chapters describing current and future risks, region-specific challenges, and success stories. More than 750 experts evaluated thousands of studies and reports to compile this latest assessment.

“We should praise the continuing hard work by public agencies and private scientists that made the Fifth National Climate Assessment possible,” said Stan Meiburg, executive director of the Sabin Family Center for Environment and Sustainability. “This Assessment reinforces the findings of previous reports that we face an enormous challenge. The challenge is ultimately not scientific or technical; it is policy.”

Before 2007, the federal government implemented voluntary programs to curtail climate change and regulatory efforts that indirectly limited greenhouse gas emissions increases in industry, according to the Congressional Research Service. To Meiburg, stronger policy is needed to spur action and reduce emissions.

“We have foreclosed many options by past inaction, so that significant warming and its consequences are already locked in,” Meiburg said. “This should only motivate us to implement measures to adapt to what we know is coming and reduce future emissions so that matters do not get even worse. As the report notes, we are making progress in reducing carbon emissions, but as a nation we must work on our own and in concert with the rest of the world to pick up the pace.”

At Wake Forest University, the pace of reductions is consistent. By the close of FY23, WFU achieved a 46% reduction in GHG emissions from a 2007 baseline. Regular investment in building renewal and energy efficiency measures, coupled with a reduction in the carbon intensity of the electrical grid, make up this progress.

Wake Forest’s current rate of reduction puts the University on track – and even ahead of schedule – to achieve its benchmark goal of a 50% reduction by 2030, in keeping with the Paris Climate Agreement. Continued investment in renewal and efficiency, coupled with investments in renewable energy, will get WFU most of the way toward our ambitious, yet attainable goal of climate neutrality by 2040.

On a national scale, efforts to adapt to climate change and reduce emissions across the country have expanded since 2018. However, the report notes that the country has seen just a 12 percent reduction in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from 2005 – 2019.

“That’s less than a percent a year at an annualized rate – at that rate it would take almost a century to hit zero emissions, which would be disastrous,” said Miles Silman, Andrew Sabin Presidential Chair of Conservation Biology. “We need to be single minded about reducing greenhouse gas emissions in the U.S. We know how to do it, now we need to do it.”