The Inextricable Link Between Human and Environmental Health

By Sophia Masciarelli, Content Development Assistant

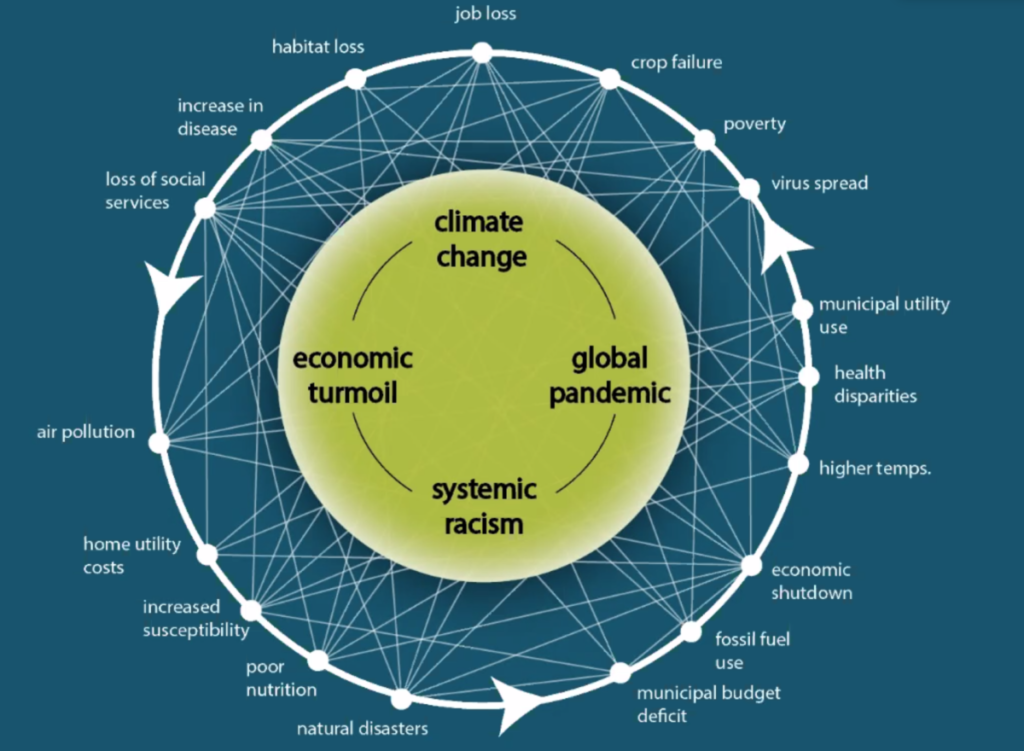

When the novel coronavirus hit the United States in early 2020, it upended every aspect of American life as we knew it. The presence of the virus also uncovered countless threads of inequity that run just below the surface, complexly interwoven and tangled. The pandemic, along with sweeping social revolution, has brought these complex entanglements to light, including the ways in which human health and environmental health intersect.

“The coronavirus pandemic is finally forcing people to understand the connection between environmental, personal, and public health, especially the role that environmental factors can play in exacerbating the dangers of a public health crisis such as this,” said Cecile Pacquette, a Wake Forest senior.

Paquette uncovered many of these connections and the localized ties to Winston-Salem through a research opportunity facilitated through the Office of Civic & Community Engagement (OCCE) this summer. She presented her research on Environmental Injustices and how they are presented in the media as part of the OCCE’s virtual panel on the intersections of human health, food access, and environmental health in September.

In her research, Paquette discovered that Winston-Salem ranked 20th worst place to live in the U.S. with Asthma, a respiratory disease that is a direct outcome of dwelling in areas of poor air quality. Black, Hispanic, and Indigenous individuals in the US face the highest burden of Asthma, according to a report by the Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America. These disparities are caused by complex factors including structural racism, leaving residents in minority communities far more at-risk of facing complications due to COVID.

“The connection between environmental health and human health, especially when it comes to the overlap with different factors including race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, is never random,” said Dr. Megan Regn, visiting Assistant Professor of Economics and moderator of the OCCE panel on food and health. “It always comes back to city planning.”

In Winston-Salem specifically, natural atmospheric circulations result in a higher concentration of pollutants and irritants settling on the eastern and southeastern region, which also align with the greatest density of Black, Latinx, and other marginalized communities of the area. This factor, in combination with access to lower access to reasonable healthcare services and lower quality of housing available, results in a tangled string of problems that are further exacerbated in the face of a respiratory pandemic.

“The U.S. is segregated, and so is pollution,” says Dr. Robert Bullard, a distinguished professor at Texas Southern University who is considered the Father of Environmental Justice.

There are endless statistics that illustrate Dr. Bullard’s point: the fact that 78% of Black Americans live within 30 miles of a coal power plant, or that communities of color are 40% more likely to have unlawfully unsafe drinking water and have far higher exposure rates to air pollution than their white, non-Hispanic counterparts. The examples across the country are countless, and continue to grow as the climate crisis progresses.

In the wake of a virus that has killed 1 in 1,000 Black Americans, a rate significantly higher than white Americans, it is critical to pay attention to the places that these factors overlap. The urgency of the COVID-19 pandemic is dual-toned, composed of long-term limited access to healthcare, poor environmental quality, and pre-existing conditions. Ultimately, the heaviest burdens are set upon the most marginalized communities with the least available resources to cope.

A 2019 study found that white people were exposed to around 17% less pollution than they created, while Hispanic people were exposed to 63% more than they created and Black people were exposed to 56% more PM2.5 than they created.

“Recent conversations on social media and in print have highlighted institutional racism that exists in government policies and practices involving education, housing, employment, and the environment,” wrote Dr. Sarah Morath of Wake Forest University School of Law in an article for Bloomberg News. Dr Morath’s latest research examines the impact of particulate matter pollution on communities of color, focusing on a region in the southeast U.S., dubbed “cancer-alley” due to severe environmental pollution and the resulting cascades on human health.

From concentrations of air pollutants to the distribution of landfills and mines throughout communities to limited access to adequate healthcare and clean water, environmental racism is deeply rooted in American society, occurring both in practice and policy. Waste sites, areas of most intense environmental pollution, and high risk environmental hazards become assigned to marginalized communities through both political neglect and deeply-rooted property ownership discrimination. To disentangle these problems requires an intersectional approach and reflection on centuries of systematic oppression that have driven us to this point.