Wake Forest University welcomes Dr. Julie Velásquez Runk as Environmental Program Director

Wake Forest University welcomed Dr. Julie Velásquez Runk as the new director of the undergraduate Environmental Program this year. She comes to Wake Forest from the University of Georgia, where she was an Associate Professor of Anthropology. Dr. Velásquez Runk completed her undergraduate studies at Grinnell College as a major in biology and minor Latin American studies. She holds a Master of Environmental Management in Resource Ecology from Duke University and a dual Ph.D. in Anthropology, Forestry & Environmental Studies and Economic Botany from Yale University and the New York Botanical Garden. She is also a research associate with the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute.

Velásquez Runk’s work is integrative and interdisciplinary: she examines the ways communities use and manage their landscapes, including scientific, conservation, Indigenous knowledge, and policy perspectives.

When asked about the interdisciplinarity of Dr. Velásquez Runk’s research and scholarship, Provost Michele Gillespie shared:

“Interdisciplinary research may be the single best tool our society has for solving today’s complex problems. Scholars who embrace interdisciplinarity know how to break down complexity into many parts. They invite diverse people, ideas, methods, knowledge bases and skill sets into a generative intellectual space to unleash collaborative critical thinking and pragmatic solution making. By analyzing information from multiple disciplines, these scholars take the best concepts from each area, and integrate them in new and creative ways to find unique solutions to our most pressing problems.”

Dr. Velásquez Runk spoke with the Office of Sustainability about the breadth of her work and her vision for the future of the Environmental Program at Wake Forest University.

Q: What most intrigued you about Wake Forest and becoming a part of the university?

A: I was intrigued by Wake Forest as a smaller university community with a liberal arts foundation, a growing student interest in environmental studies, and a commitment to Pro Humanitate. That is an unusual combination. The strength of the university is interdisciplinarity through its liberal arts college and is complemented by vibrant professional schools and graduate programs. The smallish campus community means some agility–such as faculty in different disciplines being able to co-teach at Wake Downtown–and creates uncommon opportunities for experiential learning and community co-labor. And Wake’s Pro Humanitate motto coupled with President Wente’s charge of radical collaboration let me know that my vision to cultivate just environmental futures would be valued here.

Q: Can you share a bit about your research background?

A: I consider myself to be a socio-environmental scholar, trained as both an ecologist and anthropologist who also incorporates the humanities. I also have worked inside and outside of academe, starting my career with environmental non-governmental organizations and later worked with governmental organizations.

My research has been varied and what ties it together is working with communities on what they want to do. Then they take that information and act on it. For example, as an undergraduate I worked on native species reforestation in the Monteverde area of Costa Rica with a local non-governmental organization, the Monteverde Conservation League. Farmers wanted to plant trees as windbreaks, which decreased stress of their dairy cows and increased milk production. And there also was growing tourism in the area, especially by birdwatchers. I interviewed farmers on which species they wanted to plant that would attract birds and also grow well for windbreaks. Then I did the propagation studies on their preferred species and wrote a nursery management manual summarizing the results that worked best. The League used that information to reforest with farmers. I recount that history because I know how important it was that my initial research experience was with communities as an undergraduate, rather than with what is now being called helicopter or parachute research (a more extractive pattern of research by jumping in, taking data, and leaving). I learned early on how to co-labor.

More recently, I have worked with community lead Fred Smith to bring together graduate students and African American community members in Athens, Georgia on local African American history. The entire team brainstormed the research topic and then divided up history into eras. Students and community members co-researched history in local archives, with the results stewarded by the community team. This reflects my broad approach to human-environment relationships. I also am continuing our research with an interdisciplinary team from the University of Georgia, Panama’s Gorgas Memorial Institute of Health Studies, and Indiana University to examine how vector-borne zoonotic disease transmission varies with forest cover in western Panama’s non-Indigenous communities. With funding from an NSF Dynamics of Integrated Socio-Environmental Systems grant, we are combining household surveys, ecological and veterinary assessments, participant observation, remote sensing and GIS, and historical analysis of Chagas disease and American cutaneous leishmaniasis to develop a mathematical framework for studying how deforestation, reforestation, and human activities impact zoonotic infectious disease.

Q: You have dedicated a lot of time to work and research in Panama with the Wounaan people. Can you tell us about the work you’ve done there and continue to do?

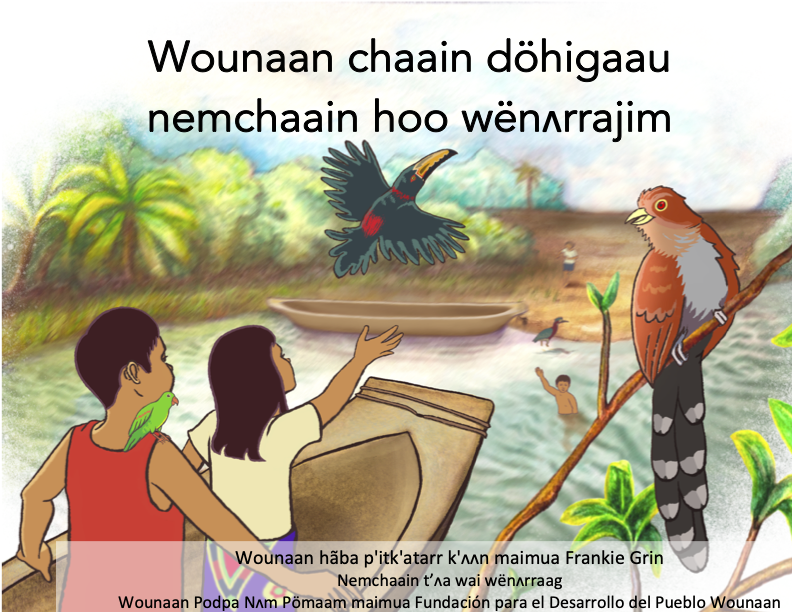

A: For over twenty-five years Indigenous Wounaan community members in Panama have taught me. They teach me, as Nishnaabeg scholar Leanne Betasamosake Simpson has said, that land is pedagogy – how to know and do through the land and waters. My work with Wounaan has been very diverse based on their interests and needs, with the Wounaan Podpa Nʌm Pömaam (the Wounaan National Congress) and the Foundation for the Development of Wounaan People involved in all stages, from planning to presenting research. Among the topics we have worked are understanding the succession of their lands after agriculture and how that mosaic of land use is obscured by remotely sensed satellite images, applied linguistics through an unusually rich sixty years of audio recordings of their traditional stories and used it for education in their schools, and addressing illegal logging and the politics of environmental governance. I continue to work with Wounaan scholars on their science, language, and culture, and we also work with their allies, such as the non-governmental organizations Native Future and the Rainforest Foundation, and their funders, such as the United Nations Development Program.

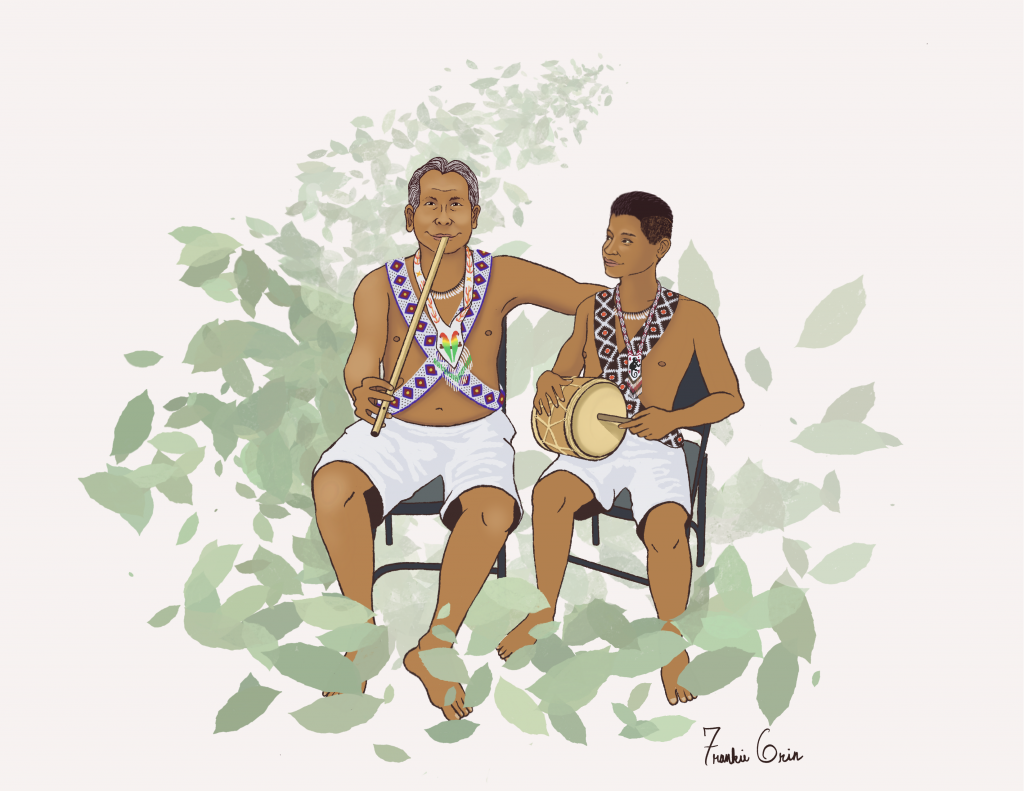

One of the works I am most proud of is our illustrated story (or children’s) book about the relationships among Wounaan and birds. The team of hapk’ʌʌn* Rito Ismare Peña, Chenier Carpio Opua, Doris Cheucarama Membache, and Chindío Peña Ismare originally wrote the story in Wounaan meu, and then we guided artist Frankie Grin on the paintings. This project was made much more difficult in the pandemic because Frankie and I could not travel to Panama and so we worked through online meetings and text and voice messages. We also suffered the loss of our esteemed colleague, hapk’ʌʌn Rito, who died of COVID as we were working on the book. As a former national chief, a traditional flautist, ritual expert, pastor, writer of their language, and friend, it was a tremendous loss. After some time, Dorindo Membora Peña joined the team and Frankie made an additional painting in dedication to our deceased colleague. We completed the book in three languages (Wounaan meu, Spanish, and English) and also made them available as digital audio books (and also in print) on the Storyjumper platform. Children can access a print book through discounted sales by the Wounaan National Congress or access it for free on Storyjumper through a smart phone (which are widely used by Wounaan). We also wrote a peer-reviewed journal article (in genealogy) about Indigenous theory and redistribution in the collaborative process of making the book.

* hapk’ʌʌn is one of many Wounaan meu honorifics for deceased people. In order to respect Wounaan tradition, the honorific is used each time a reference to Velásquez Runk’s deceased colleague is made.

Q: You mentioned that you believe in “redistribution” work (i.e. redistribution of knowledge, power, etc). Can you expand on what that means to you?

A: Yes. There is a lot of attention these days to reciprocity and giving back in research, especially environmental research. I am excited that these ideas are gaining currency. I also promote the idea of redistribution, how to redistribute what we have, particularly what we have in excess, to further equity. Redistribution is often an underacknowledged part of our socioenvironmental worlds. For example, at dusk in Wounaan communities, it is common to see children walking to friends’ or relatives’ houses with plates of food. It may be that their family went shrimping and has more shrimp than they need. But the food is often cooked, so that reveals that additional care and labor has been put into it. Wounaan taught me the everyday importance of redistributing through life and work, which complemented how my parents raised us to be committed to community and justice. I also have been inspired by ecologist Suzanne Simard’s findings that trees share nutrients with other trees at critical times, creating healthier forests. I strive to apply these ideas to how I live and research, redistributing my knowledge, my power, and my money to cultivate a more just world. In the academic world there is a growing interest in such ideas as ethics of care, carework, or caretaking.

Q: In your opinion, what is the importance of an environmental science/studies degree in the contemporary world our students are entering?

A: I see environmental science and studies as critical for all students and the degrees in them for those who are especially committed to people and environment. As your question implies, students are entering a world in which climate and environmental change are scientifically well established and we all must commit to action to mitigate them. But we cannot do that well unless we also are committed to equity and justice. College is such an important period in our lives, a rare space to dedicate ourselves to learning (including about ourselves). For those who seek an environmental science or studies degree at Wake, they also will learn to use evidence, creativity, and action to respond to socio-environmental challenges and to do so by working with others.

Q: Your academic background is centered on the liberal arts. What does an interdisciplinary liberal arts program such as our ENV program offer to students that makes it distinctive from programs at other universities?

A: Interdisciplinary liberal arts offers students the ability to understand the richness of how the world is, rather than the world as disciplined into academic silos or departments, and also how to engage issues where they live, work, and visit. For environmental studies these are crucial, as students learn about human-environment relationships by thinking across disciplinary boundaries and placed-based learning by working in and with communities. This is true in our ENV program, as students can take a class taught by geographer Rebecca Croog on supporting local environmental initiatives through participatory research or on water resources and society by geoscientist Steve Smith or on writing, wilderness, and sustainability in Alaska with writing professor Eric Stottlemyer. Additionally, the small class size at Wake really allows students the chance to learn by doing, to learn experientially, through classes, partners like the Office of Sustainability, and global programs. As a small university, ENV includes professors in the professional schools, such as the Law and Business Schools, as well as the Sustainability Graduate Program. I also saw how the benefits of a liberal arts education percolate throughout life. Among my former graduate students, those who had a liberal arts education had a jump start, as they were already innovative and interdisciplinary thinkers, superb writers, well acquainted with justice and equity, and experienced researchers.

Q: What is your vision for the future of the ENV Program at Wake?

A: My vision is for justice and community-oriented environmental studies at Wake. I hope to add to the program faculty, students, and staff coming together around multi-year community projects identified by community partners in Winston-Salem. These projects would be developed by those partners and multi-disciplinary faculty, creating spaces where students learn both the theory and practice of collaborative and inclusive environmental problem-solving. That vision draws on North Carolina’s legacy as the birthplace of environmental justice forty years ago and also synergistically applies it to work in other locales. I am grateful to the numerous ENV faculty members who are already working in Winston-Salem, as well as to the previous directors of ENV that helped to create a solid footing for such engaged work. As we move forward with that vision, we have several approaches we are working on: providing additional summer fellowship support for undergraduates in ENV, building out geographical information systems (GIS) so that students can think critically and learn experientially about environmental justice through digital mapping and satellite image analysis, strengthening networks for students with environmental employers, and hiring faculty who share a commitment to action and place-based learning. I am thrilled about the collaborative campus culture here at Wake and I look forward to working with students, staff, and faculty on partnerships for justice and community in environmental studies.